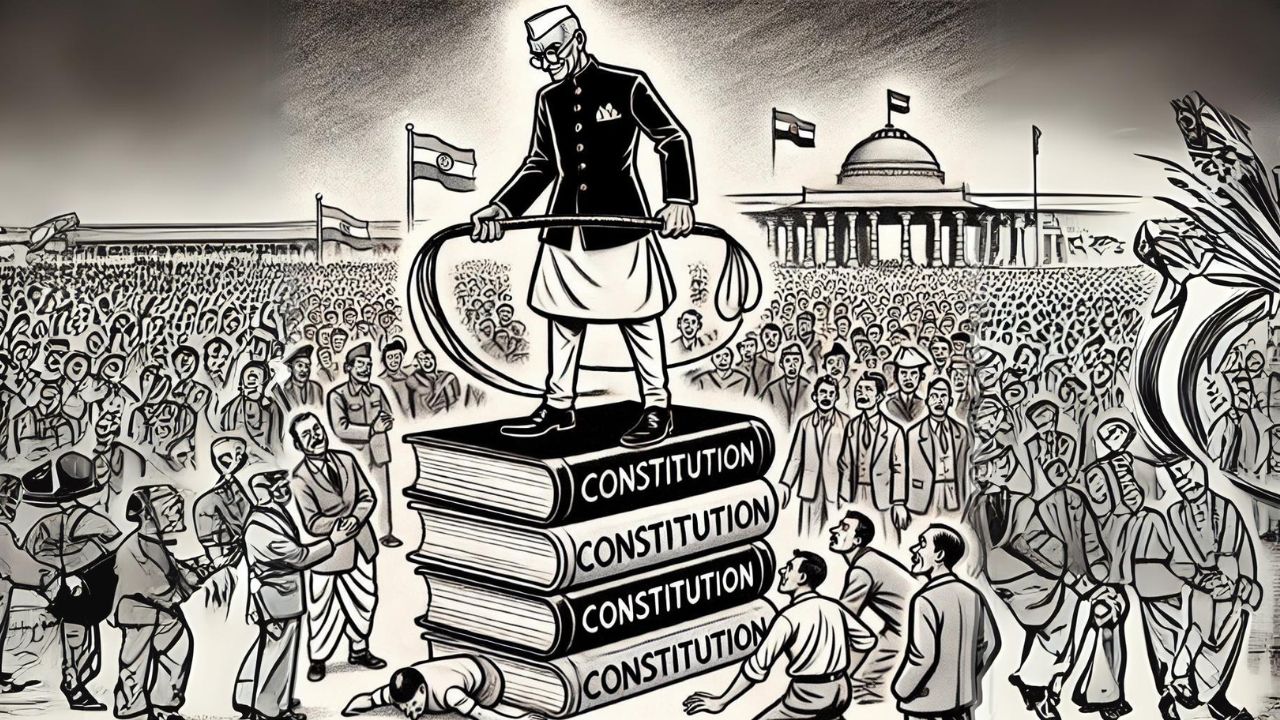

The concept of emergency provisions enshrined in the Indian Constitution represents one of the most debated and consequential aspects of India’s legal and political landscape. These provisions empower the central government to exercise extraordinary authority during crises, often at the expense of the federal structure and civil liberties. The declaration of the National Emergency in 1975 by then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi stands as a stark and controversial landmark in Indian political history, encapsulating the potential perils of unchecked power.

Understanding Emergency Provisions

The Indian Constitution, through Articles 352 to 360, delineates the framework for three types of emergencies: National Emergency, President’s Rule, and Financial Emergency.

National Emergency (Article 352): This can be declared by the President of India in the event of war, external aggression, or armed rebellion. During such an emergency, the central government gains extensive control over the states, and several fundamental rights of citizens are suspended. Initially, the Constitution allowed for the declaration of an emergency in the case of “internal disturbances,” a term that proved to be dangerously vague. This provision was later amended to “armed rebellion” by the 44th Amendment to prevent misuse.

President’s Rule (Article 356): This is imposed if the President, upon the Governor’s advice, believes that a state’s government cannot function according to constitutional provisions. This results in the central government assuming direct control of the state’s administration. This provision has been invoked numerous times, often controversially, leading to accusations of political misuse.

Financial Emergency (Article 360): This can be proclaimed if the President deems that the financial stability or credit of India, or any part thereof, is threatened. Under such an emergency, the central government is empowered to reduce salaries of government officials and give financial directives to the states. Interestingly, this provision has never been invoked in India’s history.

Historical Context and Debate

The emergency provisions sparked intense debate during the drafting of the Constitution. Fears of misuse were prevalent, with comparisons drawn to the Enabling Act in Nazi Germany that facilitated Hitler’s dictatorship. Despite these concerns, key figures like Dr. B.R. Ambedkar and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel advocated for these provisions, arguing that a strong state was essential to safeguard individual freedoms and maintain national integrity.

The National Emergency of 1975: A Dark Period

The National Emergency declared on June 25, 1975, remains a dark period in Indian democracy. Ostensibly declared to address internal disturbances and threats to national security, many believe it was primarily a political maneuver by Indira Gandhi following her conviction for electoral malpractices by the Allahabad High Court.

Immediate Causes

Several factors precipitated the declaration of the National Emergency:

- Political Pressure: The Allahabad High Court’s verdict on June 12, 1975, found Indira Gandhi guilty of electoral malpractices, disqualifying her from holding public office for six years. This verdict threatened her position as Prime Minister.

- JP Movement: Jayaprakash Narayan, a veteran freedom fighter, led a mass movement against Indira Gandhi’s government, demanding her resignation and advocating for “Total Revolution.” His call for the military and police to disregard unconstitutional orders was seen as a direct threat to the government’s authority.

- Economic Crisis: India was facing economic challenges, including high inflation, food shortages, and unemployment, which added to the public discontent.

Declaration and Implementation

On the night of June 25, 1975, the emergency was declared, and it was officially announced on June 26. Thousands of opposition leaders and activists were arrested under preventive detention laws. Fundamental rights were suspended, and press censorship was imposed. The infamous 42nd Amendment Act, often referred to as the “mini-Constitution,” was passed during this period. This amendment significantly altered the Constitution, curbing the judiciary’s power and extending the duration of legislatures.

Impact and Consequences

The impact of the emergency was profound and far-reaching:

Civil Liberties: The suspension of fundamental rights meant that citizens could not approach the courts for the enforcement of their rights. This led to widespread abuses, including arbitrary arrests and custodial torture. Political opponents and dissenters were targeted, and habeas corpus petitions were routinely dismissed.

Media Censorship: The press was heavily censored. Major newspapers like The Times of India and The Indian Express left blank spaces where articles critical of the government would have appeared. This period witnessed a significant curtailment of freedom of expression.

Forced Sterilization: Sanjay Gandhi, Indira Gandhi’s son, led a coercive sterilization campaign as part of population control measures. This campaign faced significant criticism for its brutality and lack of consent, with reports of forced sterilizations and severe human rights violations.

Political Fallout: The emergency period led to widespread disillusionment with the Congress party. In the 1977 general elections, the Congress was decisively defeated, and the Janata Party, a coalition of opposition parties, came to power. This marked the first instance of a non-Congress government in India.

Aftermath and Legacy

The emergency lasted until March 21, 1977, leading to significant political upheaval. The severe backlash against Indira Gandhi and her party in the 1977 general elections resulted in the first non-Congress government in India. This period underscored the necessity for checks and balances to prevent the misuse of emergency provisions.

In response, the 44th Amendment Act of 1978 was introduced, making it more challenging to declare a national emergency. It required the President to act on the Cabinet’s written recommendation and mandated parliamentary approval within a month. The amendment also ensured that Articles 20 and 21 (right to protection in respect of conviction for offenses and right to life and personal liberty) could not be suspended even during an emergency.

Lessons Learned

Vigilance and Accountability: The emergency highlighted the need for constant vigilance and accountability in a democracy. It underscored the importance of a free press, an independent judiciary, and robust civil society institutions. The period serves as a reminder that democratic institutions must be protected from authoritarian tendencies.

Constitutional Safeguards: The experience led to a greater appreciation for constitutional safeguards and the checks and balances necessary to prevent the concentration of power. It demonstrated the need for strong legal frameworks to protect individual rights and prevent the abuse of executive power.

Strengthening Institutions: The post-emergency period saw efforts to strengthen democratic institutions and restore public faith in the democratic process. The judiciary and media took a more assertive role in checking governmental excesses, reaffirming their roles as pillars of democracy.

Conclusion

The emergency provisions in the Indian Constitution reflect the foresight of its drafters, who recognized the need for extraordinary measures in times of crisis. However, the events of 1975 serve as a potent reminder of the potential for abuse inherent in such powers. They underscore the critical importance of balancing state empowerment with the protection of individual liberties.

The legacy of the National Emergency continues to shape India’s political and constitutional landscape, highlighting that the strength of a democracy lies in its institutions, not in its rulers. The lessons learned from this period remain relevant, emphasizing the need for vigilance, accountability, and robust safeguards to preserve the democratic ethos of the nation. The resilience of Indian democracy in the face of such challenges reaffirms the enduring spirit of its people and the robustness of its constitutional framework.