A legendary figure in the complex tapestry of India’s democratic history, Jawaharlal Nehru was a visionary leader who championed the principles of democracy and free speech. But underneath these idealistic ideas was a complicated reality of control and repression that profoundly affected the Nehruvian era. The paradox of Nehru’s legacy is a powerful example of how principles and actions can conflict when achieving liberty in a democratic setting.

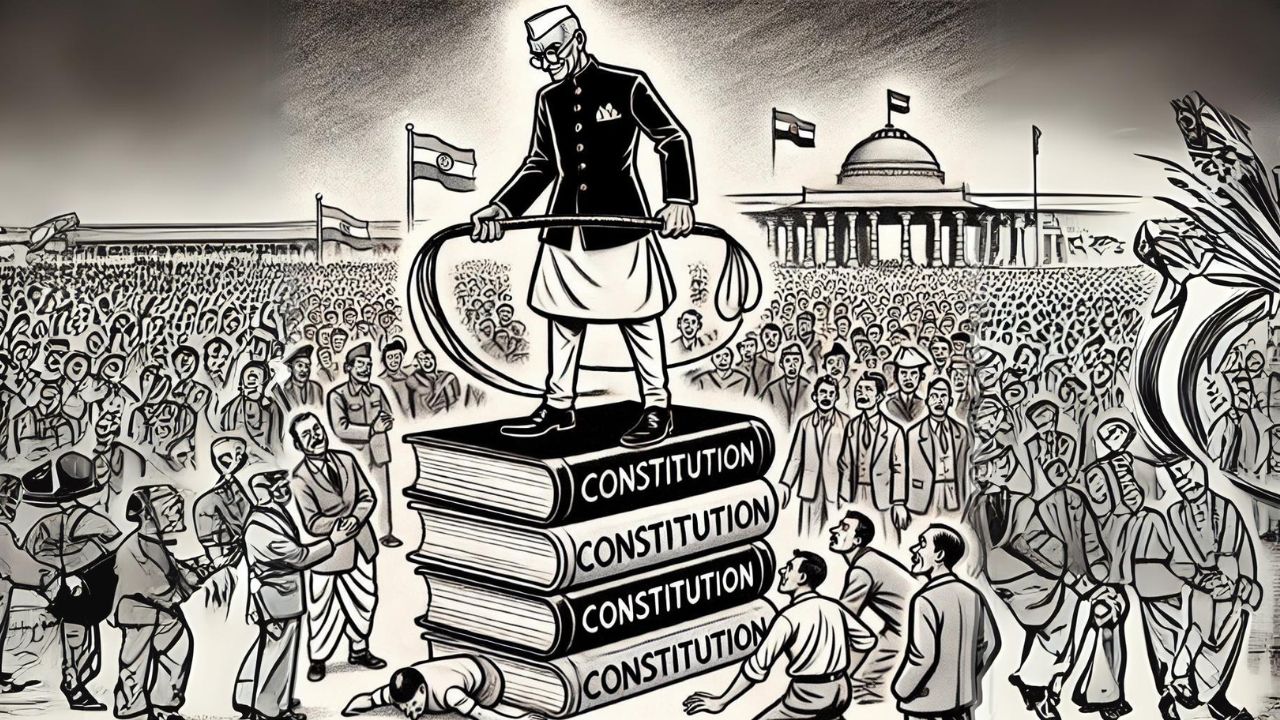

Under Nehru’s direction, the Indian Constitution’s First Amendment was drafted with the intention of putting “reasonable restrictions” on the right to free expression in order to safeguard public safety, foreign relations, and security. Its goal was to strike a balance between social stability and individual liberty, but in reality, it was frequently used as a weapon to quell dissent and muzzle critics of the status quo. This period in Indian history serves as a reminder of the need to carefully strike a balance between upholding the fundamental right to free expression and safeguarding state interests.

Majrooh Sultanpuri, the well-known poet whose bravery surpassed his poetic genius, is among the most notable instances of this paradoxical approach to freedom of speech. Sultanpuri was imprisoned after he ventured to connect Nehru with Hitler, causing a commotion in the halls of power. His year-long incarceration represents the delicate balance between political sensitivity and artistic expression that prevailed at the time. This incident demonstrates the severe restrictions placed on speech, even while a well-known individual who claimed to support it was present.

During the Nehruvian era, not only specific individuals but also entire groups and ideologies were the focus of censorship. Nehru and the Congress Party demanded that Communist parties should not be permitted to run in general elections, which put the democratically elected Communist government in Kerala in jeopardy. This was a particularly ridiculous position given Nehru’s purported dedication to democracy and plurality. The prosecution of the Communist government of Kerala is emblematic of a wider trend of intellectual suppression and reflects a deeper fear of ideological risks within the Indian political establishment.

Controlled forms of artistic expression included cinema and books. Books by writers such as Bertrand Russell were repressed or outlawed as a component of a broader campaign of intellectual persecution. Russell upended popular narratives by challenging conventional wisdom. Because of their beliefs, historians like Dharampal—whose study focused on controversial facets of Indian history—were marginalized and frequently imprisoned. The purposeful endeavor to dominate the narrative and maintain political power is indicated by the repression of dissident voices in literature and academia.

Censorship at the time also affected the state of the media. If they dared to criticize Nehru or his policies, journalists and columnists risked losing their employment or having their columns stopped. The well-known editor Durga Das is a prime illustration of the fine line separating political expediency and journalistic ethics. Because of his harsh articles regarding the Nehru family, Das was sacked. The difficulties the media encountered during this time demonstrate how difficult it is to keep an independent press in the face of governmental authority.

Censorship has a profound effect on artistic and cultural manifestations. Films that examined contentious historical events, such as “Nine Hours to Rama,” were either outlawed or subject to strict restrictions. Similar scrutiny and limitations applied to popular plays and music that questioned societal norms or the authority of the state. These illustrations show how censorship has been employed as a tactic to maintain social order and mold public opinion.

The contradiction in Nehru’s legacy lies in the stark contrast between his idealistic views of freedom and the terrible reality of repression that he oversaw. Nehru himself was a staunch advocate of free speech and criticism in democracies, despite the fact that his government regularly disregarded these principles. This contradiction between words and deeds emphasizes how difficult it is to govern a recently independent country while fending off threats from the within and the outside.

But it is important to consider this time frame in a larger context. India was managing the difficulties of national development while fending off external threats. It is crucial to preserve unity and order in this varied country, so there may have been some instances of censorship that was excessively strict due to concerns about destabilization. Nehru’s government may have restricted free speech because it was difficult to maintain stability in a nation whose people varied greatly in terms of language, religion, and culture.

But we cannot overlook the lessons of this period. It is morally and culturally respectable, as well as legally required, to defend the right to free speech and expression. Maintaining institutional integrity and protecting individual rights against abuse of power requires ongoing attention to detail. The Nehruvian era is both a cautionary tale and a call to action for democracy, demonstrating that a democracy’s real test is not its rhetoric but rather its dedication to protecting its citizens’ fundamental rights, such as the freedom to question power without fear of retaliation.

In conclusion, we should recognize the ironies that come with pursuing liberty within a democratic framework while considering Nehru’s legacy. As the ongoing fight for the right to free speech and expression serves as a constant reminder, freedom comes with a lifetime of care. The Nehruvian era provides important insights into the difficulties in striking the current balance between governmental objectives and individual liberty that democratic nations demand.

Hi, this is a comment.

To get started with moderating, editing, and deleting comments, please visit the Comments screen in the dashboard.

Commenter avatars come from Gravatar.