The Uniform Civil Code (UCC) has been a topic of considerable debate in India, both pre and post-independence. The idea behind the UCC is to replace the personal laws based on the scriptures and customs of each major religious community in India with a common set governing every citizen. This discussion has been fraught with complexity, given India’s vast diversity in culture, religion, and socio-economic conditions. This editorial seeks to delve into the historical context, legislative efforts, key milestones, and ongoing debates surrounding the UCC in post-independence India.

Historical Context

Post-independence India faced the colossal task of unifying a diverse population under a single legal and administrative framework. The framers of the Indian Constitution were acutely aware of the need to balance the secular ethos of the new republic with the religious freedoms of its citizens. Article 44 of the Directive Principles of State Policy enshrined in the Constitution reflects this balance, stating, “The State shall endeavour to secure for the citizens a uniform civil code throughout the territory of India.” However, the implementation of the UCC was deferred due to the complex socio-political landscape.

Hindu Code Bill and Early Legislative Reforms

The immediate post-independence period saw significant efforts to reform Hindu personal laws. The Hindu Code Bill, championed by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, aimed to codify and modernize the personal laws governing Hindus, Buddhists, Jains, and Sikhs. The proposed reforms included provisions for monogamy, divorce, inheritance rights for daughters, and maintenance for divorced wives.

The Hindu Code Bill faced vehement opposition from conservative factions within the Parliament, leading to its division into four separate acts: the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955; the Hindu Succession Act, 1956; the Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956; and the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956. These acts were significant in that they provided a legal framework for gender equality within the Hindu community, yet they left other religious communities governed by their personal laws.

Shah Bano Case and Its Aftermath

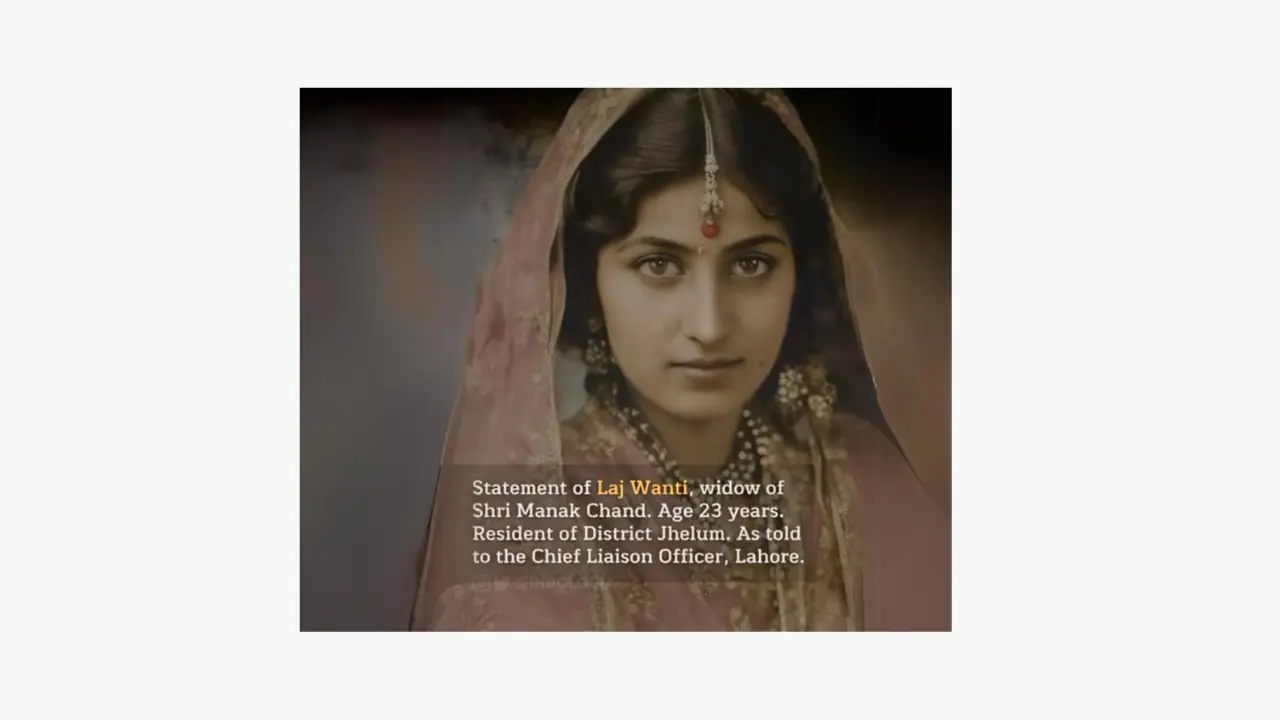

The Shah Bano case of 1985 marked a turning point in the UCC debate. Shah Bano, a 62-year-old Muslim woman, was divorced by her husband and denied alimony beyond the ‘iddat’ period (three months post-divorce), as prescribed by Islamic law. She petitioned for maintenance under Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code, which applied to all citizens irrespective of religion. The Supreme Court ruled in her favor, highlighting the discrepancies and inequalities within the Muslim Personal Law and recommending the adoption of a UCC.

The ruling triggered a political and social uproar. Conservative Muslim groups saw the verdict as an intrusion into their religious practices, leading to nationwide protests. The then-government, led by Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, succumbed to pressure and enacted the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986, which nullified the Supreme Court’s judgment and restored the primacy of Muslim Personal Law in matters of maintenance.

Recent Legislative and Political Efforts

The Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) Push for UCC

The BJP has been a strong proponent of the UCC, advocating it as a means to ensure gender justice and national integration. The party included the implementation of the UCC in its 1998 and 2019 election manifestos. In recent years, BJP leaders have reiterated their commitment to enacting a UCC, arguing that it is essential for fostering a unified legal framework in the country.

Uttarakhand’s Landmark Legislation

On February 7, 2024, the Uttarakhand Legislative Assembly passed the Uniform Civil Code of Uttarakhand Act, making it the first state in India to implement a UCC. Chief Minister Pushkar Singh Dhami hailed it as a historic moment, setting a precedent for other states to consider similar legislation. The act encompasses various aspects of personal law, including marriage, divorce, inheritance, and adoption, applying uniformly to all residents of Uttarakhand regardless of their religion.

Key Arguments For and Against the UCC

Arguments in Favor of the UCC

Equality and Justice: Proponents argue that a UCC would ensure equal treatment of all citizens, eliminating the legal disparities and discrimination inherent in the current system of personal laws.

Women’s Rights: A UCC would provide uniform rights to women across all communities, addressing issues such as polygamy, unilateral divorce, and unequal inheritance rights, thereby promoting gender equality.

Legal Uniformity: A single set of laws for all citizens would simplify the legal framework, reduce confusion, and enhance the efficiency of the judiciary.

National Integration: A UCC is seen as a means to strengthen national unity by transcending religious and cultural divides, fostering a common identity among citizens.

Modernization: By aligning personal laws with contemporary values and principles, a UCC would facilitate social progress and modernization.

Arguments Against the UCC

Religious Freedom: Critics argue that a UCC could infringe upon the fundamental right to religious freedom guaranteed by the Constitution, as personal laws are deeply rooted in religious and cultural practices.

Diversity and Pluralism: India’s vast cultural and religious diversity makes it challenging to implement a one-size-fits-all legal framework. Opponents believe that the UCC could erode the unique identities and traditions of various communities.

Practical Difficulties: The transition to a UCC would require significant changes to existing laws and practices, posing administrative and logistical challenges.

Political Opposition: The UCC faces strong resistance from various political parties and community leaders, complicating its legislative passage and implementation.

The Role of the Judiciary

The judiciary has played a crucial role in advocating for a UCC. The Supreme Court, in various judgments, has emphasized the need for a uniform civil code to ensure gender justice and national integration. In its 2017 judgment in the Shayara Bano case, which invalidated the practice of triple talaq (instant divorce) among Muslims, the Court reiterated the importance of a UCC. However, despite judicial advocacy, legislative action on the UCC has remained elusive.

The Current Status and Future Prospects

The Law Commission of India, in its 2018 consultation paper, concluded that a UCC is neither necessary nor desirable at this stage. The commission recommended a piecemeal approach, suggesting amendments to existing personal laws to address issues of gender discrimination and inequality. This pragmatic approach acknowledges the complexities involved in implementing a UCC while aiming to achieve incremental progress towards legal uniformity.

In June 2023, the 22nd Law Commission of India invited public opinion on the UCC, reflecting the ongoing deliberations and the need for broad-based consensus. The consultation process aims to gather diverse perspectives and inform future legislative efforts.

Case Study: Goa Civil Code

The state of Goa provides a unique case study as it follows a common family law, the Goa Civil Code, which is a legacy of Portuguese colonial rule. The Goa Civil Code applies uniformly to all its residents, irrespective of religion, and governs matters such as marriage, divorce, and inheritance. While it is often cited as a model for the UCC, the Goa Civil Code also includes provisions influenced by Catholic traditions, raising questions about its applicability as a nationwide model.